Elisabeth Merklein led through the interview

The text was published in edition 2 (03/25).

Reading time 5 Min.

“The truth is, we always struggle for words“

For the first time, the Bregenzer Festspiele premieres a play by Ferdinand Schmalz: In an interview, the multi-award-winning Austrian playwright talks about his extraordinary play bumm tschak oder der letzte henker that does not only guillotine grammar.

The starting point of bumm tschak oder der letzte henker seems worrying: There’s a new chancellor – and she plans to reintroduce the death penalty as her first official act. And the executioner is decided as well, although against his own will: club owner Josef. But why him?

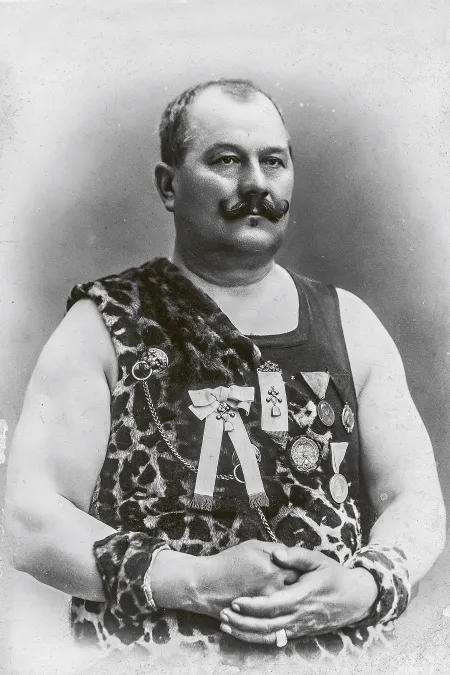

Ferdinand Schmalz: I was inspired to write this play by the life of the last executioner of the Imperial and Royal Monarchy, Josef Lang. However, it doesn’t tell his life story. Instead, it only takes up certain motives. I was intrigued by the question of why the public embraced Lang so enthusiastically: Lang became famous because of a photograph that shows him executing an Italian spy by throttling him at the gallows. Karl Kraus even had the photograph printed in the first edition of his tragedy The Last Days of Mankind. That made Lang infamous. Thousands of admirers attended his funeral. This mix of inscrutability and fame, negativity and admiration tempted me. But I couldn’t be bothered to write a big, exaggerated piece showcasing a tough, outgoing executioner – that would just minimize the whole thing too much. That’s when I had the idea to set the events in the near future, which also gives it a whole new urgency.

What is your advice for someone who unwillingly finds themselves in Josef’s situation – being pressured to do things that weigh heavy on your conscience?

My advice for everyone is: Stick to the universal principles of human co-existence. We have been fighting for centuries for general human rights and the idea of human dignity; that shouldn’t be in vain. Under no circumstances should we disregard that. Of course, it’s easy for me to say that sitting here at my desk. I think you can only know how you would decide when you find yourself in such a morally difficult situation.

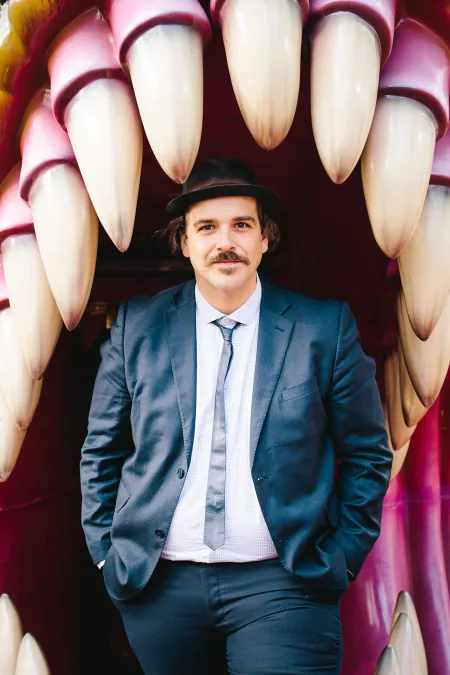

The author Ferdinand Schmalz was born in Graz as Matthias Schweiger. He studied theater, film and media as well as philosophy in Vienna where he lives until now. His first play am beispiel der butter won him the Retzhofer Dramapreis in 2013. Four years later, in 2017, he won the Ingeborg Bachmann Prize for his debut novel Mein Lieblingstier heißt Winter. In 2018, the NESTROY Theater Prize in the category best play followed for his play jedermann (stirbt), which premiered at the Burgtheater.

Did you already know how you wanted to bring your work to stage while you were writing?

I didn’t specifically think about it, so I didn’t have a definite idea of the stage design or the costumes. When I work with two strong dystopian spaces in the text like in bumm tschak oder der letzte henker – the club and the prison – I try to depict them as complete as possible. This way, the stage and costume design, the music and the production can combine it with their associations. That’s why I love the first reading so much. Suddenly, there are 30, 40 people that have all created their own fantasies about the text. And then we mix and sample it all into one evening …

The director of the Burgtheater, Stefan Bachmann, stages your work. He already directed another one of your plays, jedermann (stirbt), in 2018.

Stefan Bachmann is a director who also works with the sound of a literary text. He likes to engage intensively with the music of the verbal score. My work doesn’t solely rely on the plot but also on how the characters talk, how they stumble over words, how they rhythmize the spoken word – kind of as if there were an underlying beat from a sound system in a club, as if the words were guillotined into their syllables by this rhythm.

How did you develop this unorthodox style of speech? Do you deal with language intuitively or do you meticulously work on these sentence constructions.

A bit of both. I research a lot before I start writing to work out certain topics. But when I start writing, the first bit often just pours out of me. At that point I don’t really pay attention to construction but try to intuitively approach the sound. What follows is another phase of very hard work: proof-reading. There is something very methodical about my work with each new manuscript draft, adjusting all the little screws of such a text, making it sound whole. During this last phase I read the text out loud multiple times, I listen to what it sounds like when I read it with a lot of power until the neighbors come and ask me to tone it down a bit.

What can your language express that dictionary German can’t?

Often, we have this strange misconception that language is something fixed. That we can just open a dictionary to find out the exact meaning of a word. The truth is, we always struggle for words. It’s particularly those terms that have kept us busy ever since, such as love, death or freedom, that are not clearly defined – each generation has to come up with their own ideas for them. Especially in times of change, as we experience them now, there is a harsh fight about these terms, which is often also carried out in theater. Theater examines the subtle semantic shifts that have massive sociopolitical consequences.

You were born as Matthias Schweiger – Ferdinand Schmalz is an alias. Why did you choose this sounding stage name?

A friend of mine once caricatured me as a walrus. We had this painting hanging in the kitchen of our old flat and somehow the nickname Schmalz stuck to me. At some point, Ferdinand was added. For me, the identity of an author also carries something artistic – when I started publishing my own texts I wanted to play with this fiction and for that I needed my own name. At the time, the so-called social platforms were still very new and playing with an alter ego had become a thing. I ran a “black market for identities” with some friends in Vienna. We also had a box of usernames for social media accounts for those who wanted a quick change of identity; “Ferdinand Schmalz” was one of them. That one wasn’t sold, otherwise someone else would be sitting here right now.

18 people applied for the job of executioner in 1899, but only one seemed appropriate according to the police: coffeeshop owner and part-time executioner Josef Lang. During his term of office, he executed 39 people. Following the abolition of the death penalty, he retired in 1919. He died 21 February 1925. Many of his admirers attended his funeral in Vienna.

bumm tschak oder der letzte henker

Ferdinand Schmalz

18 July 2025 – 7.30 p.m. premiere

20, 21, 22 July 2025 – 7.30 p.m.

Theater am Kornmarkt